My experience as a neurotypical facilitator

I recently facilitated a small pilot scheme at a university to provide employability skills for autistic students aimed at supporting them through the recruitment process and beyond. I believe that I learned as much from the students as they did from me.

I approached the scheme with Daniel Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence model as my base. I supported the students to explore in a work context –

- Understanding yourself

- What others might expect from you

- How to bring your needs and expectations together with the employers’ needs and expectations.

It was evident very quickly that the students had an extremely wide range of skills, strengths and interests which went way beyond the subjects they were studying. As well as physics, geology, sociology, engineering, they had incredible skills in music, catering, tailoring, animal care, novel-writing.

The students were articulate and clear in their communications and in a ‘safe’ environment they were happy to share some of their thoughts, feelings and experiences.

One of the main challenges arising from the workshop for them in applying for jobs was matching up their expectations with the expectations of potential employers.

Below I provide my experience of the pilot group across 4 sessions and what we might learn in supporting autistic individuals through the recruitment and employment process.

Self-awareness

The first session focussed on establishing the students’ strengths, skills and areas of support-need. In many cases, the possible lack of theory of mind as expounded by Professor Uta Frith and Professor Simon Baron-Cohen, means autistic individuals do not necessarily know that prospective employers need to be told what they can offer or what they need. The students can sometimes assume the prospective employer knows without being explicitly told.

The students were asked to complete the following statements –

- My special interests are …

- The strengths I display through my special interests are …

- Other strengths I have that I am aware of are …

- The thing that distresses me most is …

- The situation I find most challenging is …

- The physical environment I find most challenging is …

- Some strategies that support me when I am anxious are …

Students were given time to process what was being asked of them and to provide their answers.

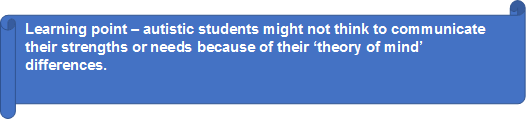

It was clear from the exercise that the word ‘situation’ was too vague and needed to be more specific. This same confusion arose in later sessions during interview practice and it was suggested to the students they should always ask for clarification where a word or phrase can be interpreted in several ways.

This exercise also allowed the students to focus on what support they might need at interview and in a job. It is very difficult for some autistic people to know what ‘reasonable adjustments’ they should ask for. It is equally difficult for employers to know what ‘reasonable adjustments’ they can offer. It will differ for every individual. Therefore, clarity from the students when they are applying for jobs is key. Some will need environmental adjustments because of sensory issues, some will need processing time adjustments, some might need to explain their stimming or other possible behaviours, for others it could be the number of people in a room. The main thing is to establish for themselves what they need and to communicate this to the prospective employer.

It was also clear that the students had many, many strengths and skills which went way beyond their chosen field of study. Again, if students can express these interests in CVs, personal statements, application forms and interviews, they can show their flexibility and diversity and break through the misperception that all autistic people are stereotypically rigid or only technically able.

The information the students came up with about themselves was then used for them to produce CVs and personal statements.

What a prospective employer might expect of you and what you might expect of them

Once the students had their list of strengths and challenges, we then moved on to expectations in Session 2.

Firstly, the students were told of their rights as prospective employees and employees within the context of the Equality Act 2010, including ‘reasonable adjustments’ and disclosure/non-disclosure. These would form their realistic expectations of an employer.

It was important to make clear to the students they do not have to disclose their diagnosis, although that would be the only way to receive ‘reasonable adjustments’. It is an entirely personal choice unless the individual is applying for certain professions such as some uniformed services, some medical services and services of national security where disclosure is required.

The bulk of the session was then spent on understanding what a prospective employer might require of the students. Again, the ‘theory of mind’ issues can make it difficult for an autistic individual to know what someone else is thinking or expecting.

We covered –

- CVs and personal statements,

- pre-interview preparation,

- interview preparation.

At every stage, we looked at what prospective employers might be expecting.

We hit a few stumbling blocks.

- The confusion caused by some forms and questions for a literal-thinking mind

- The level of honesty (or lack thereof) required during the process

We found that forms which specify ‘please delete’ are confusing, as they do not state what one is expected to delete. Similarly, forms which specify ‘please circle’ can be confusing, as quite often, an oval shape is drawn. Please tick made a lot more sense to the students.

Questions which started with ‘What would you do if …’ or ‘How would you handle …’ threw up some challenges as the scenarios were sometimes not specific enough. An example is ‘How would you deal with a difficult situation?’ This type of question is far too general. The word ‘situation’ was far too vague. They were flummoxed and they had to gain the confidence to know that it is OK to ask for clarification and to ask for examples.

A question around ‘greatest achievements’ on forms and in interviews also caused some difficulties. This was especially hard when they had to think of an achievement outside of an academic or work setting. In many ways, at work and at university achievements are more concrete. Outside of those environments achievements can depend very much on perception. We found that they all had amazing achievements outside of academic accolades – they just had not considered them as achievements. Some had pushed themselves way outside their comfort zones to try out new things; others had helped homeless friends get back on their feet; still others had passed on their skills and knowledge to young and old alike. Again, it seemed that lack of ‘theory of mind’ had prevented them from telling others about these achievements or even considered them an important part of a recruitment process.

A trickier stumbling block arose when we looked at the question ‘Why did you apply for this job?’ We started to discuss the fact that most employers would expect an applicant to ‘want’ the job. This caused some students great difficulty. Sometimes, they explained, they apply for work because they ‘need’ a job and they felt that an employer would prefer them to be honest about this. After some discussion, it was decided the best route would be for the students to apply for jobs they ‘want’ if they felt strongly about needing to be ‘honest’.

Another difficult question for them was ‘What would you like to be doing in 5 years’ time?’ Since executive functioning impairments can make it hard to plan that far ahead without knowing exactly what would be happening then, this question instigated quite a lot of discussion. The students also wanted to know why a prospective employer would ask this question if they knew the students’ fields of study? Surely, what they would be doing was obvious. We agreed they could say something about continuing in their field of study and also that they would wish to include their hobbies and interests in their lives.

How to marry your expectations with the expectations of a prospective employer in an interview

The third and fourth sessions were spent preparing for interview. We looked at ensuring the students’ CVs, personal statements and interview answers would fit together and were of the right format. We looked at preparing for an interview including finding out beforehand about the interview venue, about the ‘culture’ of the organisation by looking at the website and about dress code.

We discussed what an employer would expect during an interview. We spoke about the importance of first impressions, how to greet the interviewers and how to leave the interview.

We practised common interview questions and we explored behaviour during the interview.

As expected, three of the main challenges for the students were

- eye contact – too little or too much

- repetitive movement

- nerves and anxiety

As concentration on directing the eyes to the right place or on stopping repetitive behaviours could impact too negatively on the ability to answer questions, we agreed that it would be best to be up front with the interviewers – with or without disclosure. We felt the students might say something along the lines – ‘If you notice that I am looking away (or looking intensely) when answering your questions, it is because I am concentrating on giving you the best answer’. It is best not to leave an interviewer wondering about a behaviour they might not expect as the norm.

Repetitive behaviour or stimming might also need explaining. One student with Tourettes quite understandably stated that he always tells the interviewers beforehand because the behaviour is clearly outside what an interviewer would normally expect. However, the behaviour might not be so obvious. In this particular small group, two of the students spent the whole mock interview stroking one of their arms. In this case, just mentioning ‘I am a little nervous’ could explain the behaviour. The main thing is for the students to be aware of any unexpected behaviour they might be displaying. This might need to be pointed out to them by another person.

Nerves and anxiety play a part in every person’s interview; however, they play an even bigger part for an autistic interviewee. An autistic interviewee has to process a lot of new information before they even begin to answer the questions – they worry about how to get to the venue, what the building environment will be like, possible sensory overloads, who to look at or speak to if there is a panel of interviewers, what is expected of them in group exercises.

As well as preparing the interview questions, the autistic interviewee has to prepare and familiarise themselves as much as possible with the organisation they are going to – the place and the people. They should be supported to be confident enough to ask beforehand about the format of the interview and about the interviewers.

Some feedback on the highlights of the course from the organiser and the students:

Dr Sharon Elley – “Watching students grow and develop. Feeling that the practical delivery was the best method to achieve goals.”

Student – “The tremendous discourse. I was won over from my original mindset of attending merely to fill out the numbers.”

Student – “The worksheets. Everyone was friendly. The environment.”

Student – “The relief of doing well in my mock interview and hearing useful ideas relating to difficulties I have regarding employability.”

Conclusion

It is without doubt that autistic students need support when it comes to trying to get a job.

The support they need with the recruitment process can sometimes seem trivial but would make a huge difference to them and would enable all prospective employees, ie

- Clarity in communication at every stage

- Reducing vagueness and ambiguity

- Providing an anxiety-reducing environment

- Providing clear instructions and information on what is expected

I was overwhelmed by how much the students in this pilot group can offer to employers both from a technical point of view (how well they can do the job) and also in introducing diverse interests into the workplace.

Thanks to the enthusiasm of people like Dr Sharon Elley employability schemes such as this one will continue to support autistic students into employment.